The Writing Zone: Stage 13b - Getting Copyright Permissions

Last week I went into extensive detail on copyright infringement as a legal concept, when it occurs, and where the 'Fair Use' Doctrine comes into play.

We aren't going to waste any time, so let's get right down to business. To continue the discussion on copyright, we'll explore the process of obtaining permissions from copyright holders, the steps one would take to achieve this, and the pros and cons of being given the green light for using another's copyrighted content.

But before you begin tracking down copyright owners, it is worth knowing what is defined within a permission agreement. Understanding this is key to understanding what exactly you'll be asking for when that time comes.

Parts of a Permission Agreement

Exclusivity vs Nonexclusivity

- Exclusive agreements permits you - and only you - to use the work as described in the agreement. For example, if you have an agreement over a paragraph of text in a book, nobody else can quote that particular paragraph.

- Nonexclusive agreements permit you to use the work as described, but other can also request permission to use that same piece of work as well. For example, if you have the rights to use a photo for your book cover, that photo can still be used by other people in other nonexclusive agreements. This is the most common permission request.

Terms of Use

This defines the length of time for which you are permitted to use a work. If no limitation is defined, then you are allowed to use the permitted material for as long as you want unless the copyright holder revokes the permission. This is also known as "in perpetuity." If terms of use are granted "irrevocably," that means the copyright holder cannot revoke the permission rights once it is enacted.

Territory

Sometimes the permissions you are limited to a geographic region. A simple example: You can only use a particular picture for your book cover within the United States - all other regions outside of the US would require a different picture.

1. Identify the Owner

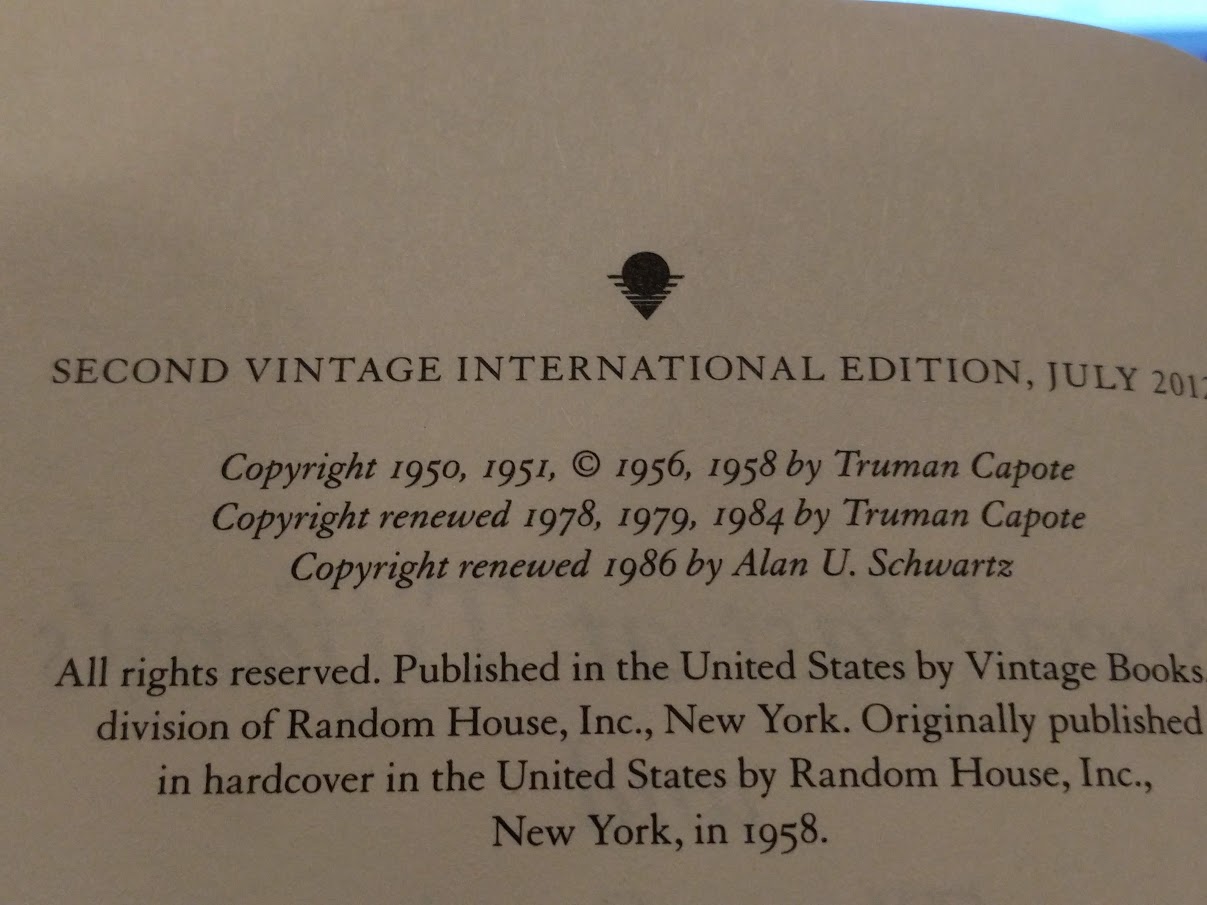

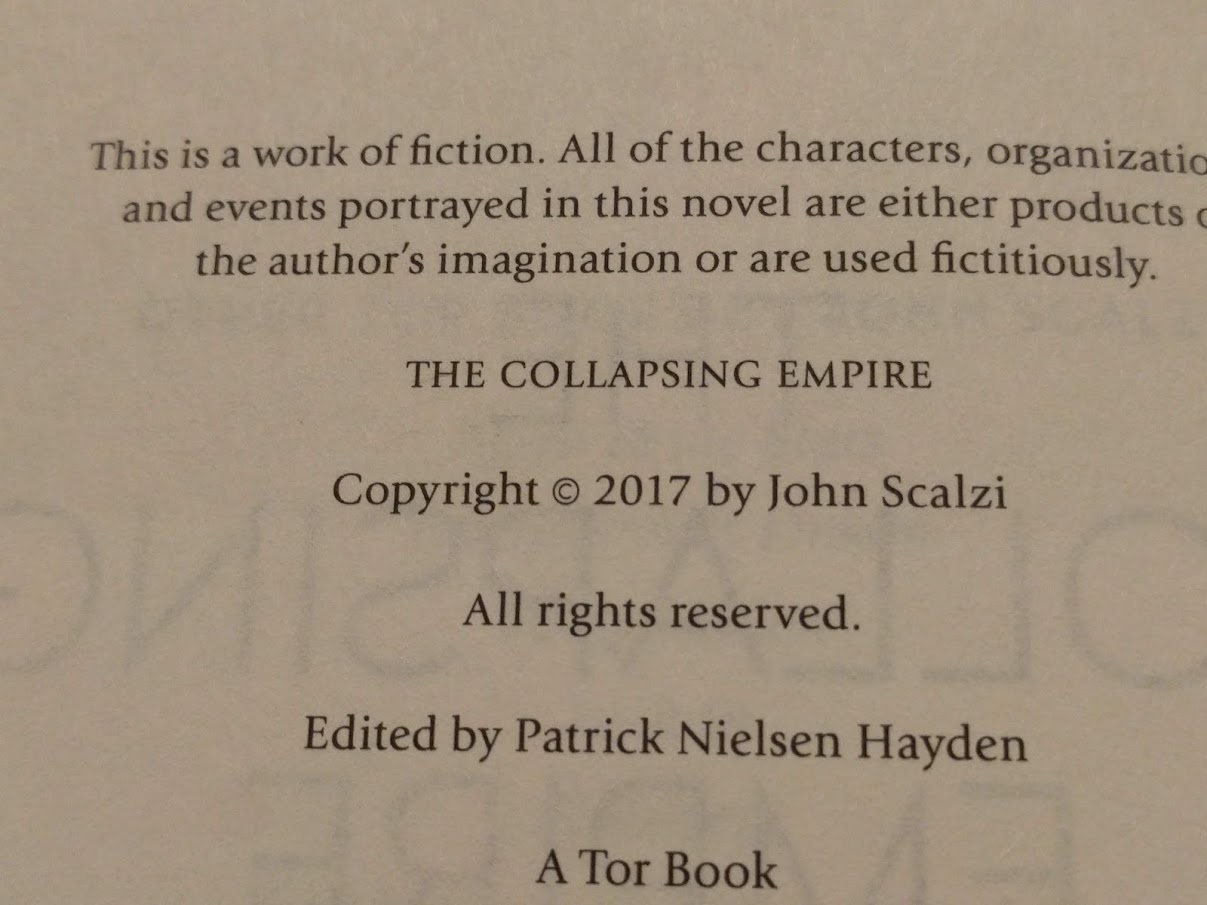

Sounds simple, right? Sometimes it can be as simple as flipping to the front of a book to locate the owner of the work you aim to quote or reference. For music and movies, it can be a bit more complicated due to the number of people and organizations that are usually involved in the production and release of such media. In the case of music, for example, copyright ownership usually is in the hands of the song's publisher - but you may also be required to contact the artist directly or their record company.

2. Prepare to Share Information

Once you know who you should be talking to, establish communications with them, whether it's via email or through an online form (you'll see options like this when working with larger publishers). Once they reply, be ready to answer any questions they have regarding the request. For books, expect questions related to where you expect the book will sell, the publisher, and possibly even the pages in the novel where the quoted/referenced material will appear.

3. Payment Requirements

Here is where many people can get tripped up. Though the common assumption here is that payment must equate to cash exchanging hands, that isn't always the case.

- Some copyright holders may simply ask for nothing more than credit (their name being mentioned in the book) in return for using their work.

- Artists and musicians may not require payment unless your book becomes profitable. Similar payment conditions could be established where you would pay nothing unless certain criteria were met in the future.

- If you are quoting very little from a book, or if what you are referencing is determined by the copyright holder to be minor, no payment may be required.

Another way to view the payment question: Permission fees are linked with the anticipated reach of your work.

4. Lock It All Down in a Contract

No matter the circumstance, always make sure to have all the terms of your permissions agreement in writing.

Some Additional Tips:

- Plan for up to three months between initiating contact with a copyright holder and finalizing a permissions agreement, especially if you're contacting a larger organization. None of this will happen overnight.

- Be prepared to write out your copyrighted content. There is always the possibility that, in the end, you'll be forced to remove the very content you sought permission to use. This can occur for any number of reasons, from the requested price being too high to the copyright holder simply denying you permission right out of the gate. Either way, the results will be the same: you'll have to invest more time an energy toward replacing that content, if not writing it out altogether.

I hope that between last week's post and everything you've read today, you have a thorough understanding of copyright law and what it means to potentially infringe on another's copyrighted work - and how to obtain permission if absolutely necessary. Most writers do not encounter situations where this becomes an issue, but the moment you consider creating a story that takes place in contemporary times, the odds of you wanting to reference something that works REALLY WELL for your story - but happens to be copyrighted - increases. Will do actually make that jump? It all depends on the story, of course, but at least with you being armed with the knowledge on copyright, you'll be ready and know what to expect.